Gorilla Poaching Statistics 2026: Shocking Numbers & Real Threats

Gorilla poaching statistics reveal a sharp decline in gorilla populations due to illegal hunting, habitat loss, and wildlife trafficking.

Fewer than 1,100 mountain gorillas remain in the wild, while eastern lowland gorillas have dropped to under 4,000, mainly because of poaching and armed conflict.

Poachers target gorillas for bushmeat, trophies, and the illegal wildlife trade, often killing entire families. Conservation patrols have reduced poaching rates in protected parks, but unprotected forests remain high-risk zones.

Stronger law enforcement, community education, and sustainable tourism are critical to stopping gorilla poaching and preventing extinction.

In the dense, mist-shrouded bamboo groves of Virunga National Park, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, a heart-wrenching discovery unfolded on March 11, 2025.

Community trackers spotted a young mountain gorilla named Fazili from the Bageni family entangled in a deadly poacher’s snare. The wire had bitten deep into his hand, threatening severe infection and loss of limb—or worse, his life.

Amid escalating clashes with the M23 rebel group, which had occupied large swaths of the park since early 2025 and forced the closure of many ranger patrol posts, quick action was critical.

Virunga’s monitoring team and veterinarians from Gorilla Doctors responded rapidly, sedating the infant, carefully removing the snare, amputating two damaged fingers, and providing urgent medical care.

Miraculously, Fazili recovered and rejoined his family troop, a testament to the tireless efforts of conservationists in one of the world’s most volatile regions.

This incident highlights the persistent danger facing mountain gorillas, despite remarkable conservation successes.

These critically endangered great apes number only around 1,063 individuals worldwide as of the latest comprehensive estimates (from 2018-2019 censuses, with ongoing monitoring confirming stability or slight growth into 2025-2026).

This figure represents a significant rebound—up from a low of about 620 in 1989—thanks to dedicated anti-poaching patrols, habitat protection, and veterinary interventions.

Yet poaching, often through indiscriminate snares set for other animals, remains a lethal threat, particularly in conflict zones like Virunga where reduced patrols allow illegal activities to surge.

Gorilla poaching statistics encompass data on illegal hunting, trapping (especially snares), captures for the pet trade, and killings for bushmeat, trophies, or traditional medicine.

These primarily affect mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei) in the Virunga Massif (spanning DRC, Rwanda, and Uganda) and Bwindi Impenetrable National Park (Uganda), as well as eastern lowland gorillas in broader DRC regions.

Direct killings are rare due to strong protections, but snares cause many injuries and deaths, with incidents spiking in insecure areas.

This article explores the full scope of gorilla poaching in depth.

You’ll discover its historical roots, from early trophy hunting to modern conflict-driven threats; current statistics and trends in 2025-2026, including regional breakdowns; the underlying causes fueling poachers; the devastating impacts on populations and ecosystems; successful anti-poaching strategies that have driven recovery; the future outlook amid ongoing challenges; and practical ways you can help, from supporting organizations to choosing sustainable tourism.

By understanding these realities, readers gain the knowledge to advocate effectively, donate to frontline efforts, or engage in responsible gorilla trekking—ensuring these gentle giants continue their remarkable comeback against the odds.

Here are powerful visuals of the resilience and vulnerability of mountain gorillas in their misty Virunga habitat:

And glimpses of rangers removing snares to protect gorilla families:

These images underscore the urgency and hope in the fight against poaching. Read on to uncover the data, stories, and actions that shape the future of gorillas.

The History of Gorilla Poaching

The history of gorilla poaching is a tragic chronicle of human exploitation intersecting with conservation triumphs, spanning over a century in the dense forests of Central Africa.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, European explorers and scientists fueled a wave of trophy hunting and specimen collection. From the subspecies’ discovery in 1902 by German Captain Robert von Beringe, mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei) became targets for museums and private collectors.

Pre-1960s, over 50 gorillas were killed by hunters and researchers alone, often for skulls, skins, or live captures to supply zoos. This era’s direct targeting, driven by colonial curiosity and prestige, decimated isolated populations in the Virunga Volcanoes region, with little regard for sustainability.

Early protections, like the establishment of Albert National Park (now Virunga) in 1925, offered minimal enforcement against these incursions.

The poaching crisis peaked from the 1960s to the 1990s, evolving into more insidious threats amid socio-economic turmoil. The bushmeat trade surged as local communities, facing poverty, hunted gorillas for protein-rich meat, a delicacy in some cultures. Infant captures for the illegal pet trade compounded losses, often requiring the killing of protective adults—up to several per infant.

Wars exacerbated the carnage: The Rwandan Civil War and 1994 genocide disrupted patrols in Volcanoes National Park, while ongoing conflicts in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) allowed armed militias to exploit Virunga for resources.

Habitat destruction from logging and charcoal production opened forests to poachers, and disease outbreaks like Ebola further thinned herds.

By the late 1980s, Virunga populations plummeted below 300, with global counts hitting a nadir of around 620 in 1989, prompting critical endangerment listings.

Pivotal events underscore this perilous period. Dian Fossey’s groundbreaking anti-poaching work from 1967 to 1985 at Karisoke Research Center in Rwanda revolutionized conservation.

She habituated gorillas for study while actively dismantling snares and confronting poachers, but her efforts highlighted dangers—her 1985 murder, likely by poachers, galvanized global attention.

The 1978 slaying of silverback Digit and five others in Rwanda shocked the world, spurring funding for patrols. In 2007, a devastating attack in Virunga killed one silverback and three females from the Rugendo family, linked to illegal charcoal trade and rebel activities, drawing international outrage.

Milestones in response include the 1991 formation of the International Gorilla Conservation Programme (IGCP), uniting DRC, Rwanda, and Uganda for cross-border anti-poaching and habitat efforts.

This collaboration, alongside intensified ranger training and community programs, began reversing declines. By 2018, sustained successes led the IUCN to reclassify mountain gorillas from Critically Endangered to Endangered, with populations surpassing 1,000—a 73% rise since 1989.

To illustrate this timeline:

| Year | Key Event | Impact on Poaching/Gorillas |

|---|---|---|

| 1960s | Trophy hunting peaks | 50+ gorillas killed |

| 1989 | Population ~620 | Heightened awareness |

| 2007 | Virunga killings | 4 gorillas poached |

| 2015-2018 | 50+ incidents in Virunga | Injuries from snares |

| 2025 | Fazili rescue amid conflicts | Ongoing threats in DRC |

Over time, poaching has shifted from deliberate trophy or pet targeting to incidental snaring. Early direct hunts gave way to opportunistic bushmeat snares set for antelope or pigs, which inadvertently maim gorillas—accounting for 80% of modern threats.

This evolution reflects broader issues like poverty and conflict, but also progress:

As awareness grew, targeted killings dropped, with rescues like 2025’s Fazili amid M23 unrest symbolizing resilient conservation amid persistent dangers.

By 2026, while populations hold steady, vigilance remains key against these enduring shadows.

Current Gorilla Poaching Statistics and Trends

In the 2020s, mountain gorilla populations have shown remarkable stability and gradual growth, a testament to decades of intensive conservation.

As of early 2026, the global wild population stands at approximately 1,063 individuals, based on the most recent comprehensive data from 2018-2024 surveys and ongoing monitoring.

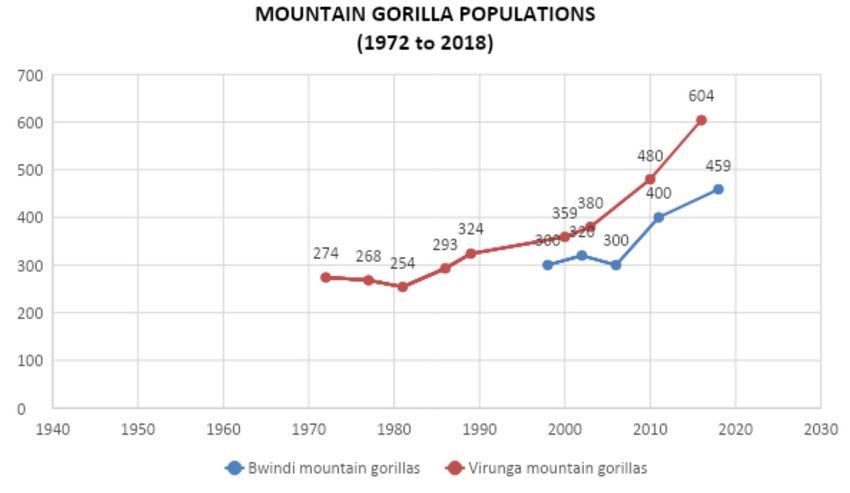

This includes around 604 in the Virunga Massif (spanning DRC, Rwanda, and Uganda) and about 459 in Uganda’s Bwindi Impenetrable National Park and Sarambwe Reserve.

A new census launched in May 2025 for Bwindi-Sarambwe, with fieldwork completed in phases through late 2025, is expected to provide updated figures later in 2026, but preliminary reports indicate continued stability or slight increases due to high birth rates and low infant mortality.

This represents a slow but steady annual growth rate of around 3-4% in protected areas, driven by anti-poaching patrols and community programs.

Poaching incidents remain low compared to historical peaks, with direct targeted killings extremely rare thanks to robust protections.

Notable exceptions include the 2020 killing of silverback Rafiki in Uganda’s Bwindi by a poacher seeking bushmeat. However, incidental threats persist: Between 2015 and 2018, over 50 snare-related incidents were recorded in Virunga alone, causing injuries or deaths.

In 2025, poaching intensified in M23 rebel-occupied sections of Virunga, where reduced ranger access led to spikes in illegal activities, including snares and bushmeat hunting.

Rangers removed hundreds of snares annually, but conflict zones saw heightened risks, mirroring COVID-era setbacks when tourism halts reduced funding and patrols.

In a broader global context, great apes (including gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos, and orangutans) face significant illegal trade pressures.

Estimates suggest nearly 3,000 great apes are lost annually to poaching and trafficking, fueling a black market valued at billions—part of the overall illegal wildlife trade worth $7-23 billion yearly.

For gorillas specifically, quantification is challenging due to their protected status and low numbers, but infant gorillas can fetch up to $250,000-$400,000 on the black market for pets or zoos, with body parts used in traditional medicine.

In contrast to high-profile species like elephants (20,000 poached yearly) or rhinos, gorilla poaching is less volume-driven but highly impactful on small populations.

Regional Breakdown

Poaching varies significantly by region, with the Democratic Republic of Congo bearing the heaviest burden due to ongoing instability.

Virunga National Park, home to over half the Virunga Massif gorillas, experiences the highest threats from armed groups like M23, which controlled parts of the park in 2025, facilitating poaching, deforestation, and charcoal production.

In Rwanda’s Volcanoes National Park and Uganda’s Bwindi/Mgahinga, incidents are minimal, thanks to strong tourism revenue funding patrols—gorilla trekking permits generate millions annually for conservation.

Cross-border efforts via the International Gorilla Conservation Programme (IGCP) help, but DRC’s conflicts make it the hotspot, accounting for the majority of snare removals and ranger fatalities.

Here’s a quick regional snapshot:

| Region | Gorilla Subpopulation | Key Poaching Threats (2020s) | Estimated Incidents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virunga Massif (DRC/Rwanda/Uganda) | ~604 | Snares, conflict-driven bushmeat, militias | 50+ (2015-2018); spikes in 2025 M23 areas |

| Bwindi-Sarambwe (Uganda) | ~459 | Rare snares, human-wildlife conflict | Low; isolated cases like Rafiki (2020) |

Types of Poaching

Snares dominate, comprising about 80% of threats—indiscriminate wire loops set for antelope or pigs that entangle gorillas, causing severe injuries, infections, or slow deaths.

Direct killings for bushmeat or trophies are infrequent, while live captures for the pet trade are opportunistic and rare for mountain gorillas due to their habitat and protections.

Traditional medicine uses (e.g., hands or heads as charms) persist in some areas but are declining.

Overall trends are encouraging: Poaching pressure has declined significantly due to conservation successes, with population growth outpacing losses in stable years.

However, disruptions like the COVID-19 pandemic (reduced patrols and tourism) and 2025’s M23 escalation caused temporary increases in risks.

The iconic population recovery is visualized in this growth infographic from WWF, showing the dramatic rise over 30+ years of efforts:

These statistics underscore a fragile success—poaching is controlled but not eradicated, requiring sustained vigilance to maintain the upward trajectory into 2026 and beyond.

Causes and Drivers of Gorilla Poaching

Gorilla poaching is driven by a complex interplay of direct motives and broader external factors, rooted in socio-economic pressures and cultural practices across Central Africa.

While direct killings have declined due to conservation efforts, incidental and opportunistic threats persist, threatening the fragile recovery of mountain gorillas.

Understanding these drivers is crucial for targeted interventions, as poaching continues to undermine populations despite global numbers stabilizing around 1,063 in 2026.

Primary motives include the bushmeat trade, where gorilla meat is considered a delicacy and status symbol in parts of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Rural communities, facing food insecurity, hunt gorillas for protein, with consumption deeply embedded in local diets.

The illegal pet trade targets infants, often requiring the slaughter of protective adults, with young gorillas sold as exotic pets or to zoos on the black market.

Traditional medicine further fuels demand, using body parts like hands, heads, or bones as charms believed to confer strength, fertility, or protection—practices prevalent in West and Central Africa.

External factors exacerbate these motives.

Widespread poverty drives communities to rely on wildlife for income and sustenance, with limited alternatives pushing illegal hunting.

Logging and deforestation provide access to remote forests, facilitating poacher incursions and habitat fragmentation. Armed conflicts, particularly in eastern DRC, create lawless zones where militias like M23 exploit resources, displacing rangers and enabling unchecked poaching.

Key drivers can be categorized as follows:

- Economic: High black market value, with gorilla parts fetching premium prices in illegal trade networks, incentivizing poachers amid poverty.

- Cultural: Beliefs in magical properties of gorilla remains, used in rituals and medicine, perpetuating demand despite legal bans.

- Incidental: Snares set for other wildlife, like antelope, inadvertently trap gorillas, causing 80% of injuries and deaths in recent years.

The 2025 surge in M23-occupied zones of Virunga National Park exemplifies these dynamics. In January 2025, M23 rebels, backed by Rwanda, seized Goma and expanded control, closing patrol posts and intensifying poaching.

By April, incidents like the snaring of young gorilla Fazili highlighted the crisis, with reduced ranger presence allowing militias to hunt for bushmeat and profit from chaos.

Conflict-driven displacement amplified poverty, boosting illegal activities, while noise and deforestation disrupted gorilla behavior. This surge reversed local gains, underscoring how instability intertwines with economic and cultural drivers to threaten conservation.

Addressing these requires holistic approaches: alternative livelihoods, community education, and conflict resolution to curb demand and access.

Impacts of Poaching on Gorilla Populations and Ecosystems

Poaching inflicts profound, cascading damage on mountain gorilla populations and their ecosystems, despite overall population recovery to around 1,063 individuals by 2026.

While direct killings are rare, snares and opportunistic hunting cause chronic losses, disrupting social structures and threatening long-term viability.

These effects extend beyond individual gorillas to broader ecological and economic consequences in the Virunga Massif and Bwindi regions.

Directly, poaching drives local population declines through fatalities and reduced reproductive success. Snares often lead to severe injuries, infections, or amputations, lowering survival rates and fertility.

More devastating are targeted killings, particularly of silverbacks—the dominant males who protect groups and sire most offspring.

Their loss triggers social upheaval: new males may commit infanticide to bring females into estrus, orphaning infants and destabilizing family units.

A stark example is the 2007 Virunga killings, where poachers slaughtered one silverback and three adult females from the Rugendo group, leaving several young orphaned and the family fragmented.

Such events not only reduce numbers but also erode genetic diversity, making surviving populations more susceptible to inbreeding and disease.

These disruptions ripple through ecosystems. Gorillas are keystone seed dispersers, consuming fruits and spreading seeds via dung, which promotes forest regeneration and biodiversity.

The loss of individuals—especially breeding adults—reduces this vital service, leading to habitat imbalance as certain plant species decline.

In fragmented forests, this exacerbates vulnerability to invasive species and climate change impacts, threatening the rich biodiversity of the Albertine Rift, home to over 1,000 plant and animal species.

Economically, poaching undermines gorilla-based tourism, a cornerstone of local economies in Rwanda and Uganda.

Permits for gorilla trekking generate tens of millions annually—Rwanda alone earns over $100 million from tourism, with gorilla experiences contributing significantly through permits ($1,500 per person) and related services.

Declines in tourism revenue, as seen post-COVID when visits plummeted and conservation funding dropped, weaken anti-poaching patrols and increase poaching risks in a vicious cycle.

The table below summarizes these impacts:

| Impact | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic | Loss of silverbacks and breeding adults | 2007 Virunga event |

| Ecological | Habitat imbalance from reduced seed dispersal | Reduced forest regeneration |

| Economic | Tourism decline | Post-COVID risks |

A stable gorilla family group highlights what is at stake when poaching strikes:

Tourism brings visitors close to these majestic animals, supporting conservation:

Ultimately, these interconnected impacts underscore that protecting gorillas safeguards entire ecosystems and economies. Sustained anti-poaching efforts are essential to prevent irreversible losses.

Anti-Poaching Efforts and Successes

Mountain gorilla conservation stands as one of the world’s most inspiring success stories, driven by collaborative, multi-faceted anti-poaching efforts that have turned the tide against extinction.

Central to this progress is the International Gorilla Conservation Programme (IGCP), a unique coalition of WWF, Fauna & Flora International, and Conservation International.

Established in 1991, IGCP fosters transboundary collaboration across Rwanda, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), supporting ranger capacity, habitat management, and community engagement.

Through IGCP, partners coordinate censuses, promote responsible tourism, and implement integrated strategies that have enhanced regional cooperation and reduced threats like poaching and habitat loss.

WWF plays a pivotal role, providing training in modern anti-poaching techniques, equipment for patrols, and support for snare removal across gorilla ranges.

In Virunga and beyond, WWF-backed initiatives have empowered local authorities to monitor populations and combat illegal activities, contributing to habitat security and community benefits.

At the frontline, ranger patrols form the backbone of protection. In Virunga National Park alone, over 2,200 patrols occur annually in gorilla sectors—averaging six daily—where rangers dismantle snares, monitor health, and deter intruders.

These “extreme conservation” efforts involve daily tracking, veterinary interventions, and rapid responses. Tragically, this work comes at a high cost:

Since 1925, more than 220 Virunga rangers have been killed in the line of duty, many in ambushes by militias amid ongoing conflicts. Despite these sacrifices, their dedication has proven indispensable.

Key successes highlight the impact: Mountain gorilla populations have grown by 73% since 1989, rising from around 620 to over 1,063 individuals today, with stable or increasing trends in 2025-2026.

This rebound—reclassifying the subspecies from Critically Endangered to Endangered in 2018—stems from reduced poaching, veterinary care, and tourism revenue funding patrols.

High-profile rescues underscore ongoing vigilance: In March 2025, young gorilla Fazili from the Bageni family was freed from a snare in Virunga amid M23 conflicts.

Community trackers spotted him, and rapid intervention by Virunga’s monitoring team and Gorilla Doctors removed the snare, amputated damaged fingers, and ensured his return to the troop.

Technology amplifies these efforts: Drones scan vast terrains for illegal camps and snares, enabling precise surveillance in remote or conflict zones without disturbing gorillas.

WWF and IGCP have deployed drones to cover hundreds of square kilometers, supporting censuses and rapid responses.

Community programs further strengthen success by addressing root causes: IGCP and partners promote alternative livelihoods like beekeeping and eco-tourism, reducing poaching incentives through shared benefits and education.

These combined strategies—international collaboration, heroic ranger work, innovative tech, and community involvement—demonstrate that sustained, adaptive conservation works, even in volatile regions.

Mountain gorillas’ recovery offers hope, proving that collective action can secure a future for endangered species.

Future Outlook and Projections for 2026 and Beyond

As we move through 2026 and look toward the decade ahead, the future of mountain gorillas remains cautiously optimistic, built on the hard-won gains of the past four decades.

With the global population holding steady at approximately 1,063 individuals and showing consistent annual growth of 3–4% in protected areas, experts anticipate continued stability through 2026 and into the late 2020s—provided key threats are managed effectively.

The most critical variable is regional security. If armed conflicts in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, particularly M23-related instability in Virunga National Park, begin to ease or are contained, ranger patrols can expand, snare removal can intensify, and habitat monitoring can return to pre-conflict levels.

Such de-escalation would likely sustain or even accelerate population growth, allowing more family groups to thrive and reproduce without interruption.

However, significant risks loom. Climate change is already shifting vegetation patterns in the Virunga Massif and Bwindi, pushing gorilla ranges to higher, cooler altitudes where food availability and habitat quality may decline.

Increased human encroachment—driven by population growth, agricultural expansion, and illegal logging—continues to fragment forests and heighten human-gorilla conflict.

Diseases transmitted from humans or livestock also remain a persistent danger, especially in areas with reduced veterinary surveillance during unrest.

If current conservation momentum is maintained—through sustained funding for the International Gorilla Conservation Programme (IGCP), WWF, Gorilla Doctors, and national park authorities—projections suggest the population could surpass 1,100 individuals by 2030 and potentially approach 1,200–1,300 by the mid-2030s. This would represent a continuation of the remarkable 73% recovery since 1989.

Here are striking visuals of mountain gorilla families thriving in their misty habitat, symbolizing the hope for the future:

And a young gorilla playfully interacting with its family, a reminder of the generations we must protect:

The trajectory is clear: with continued international support, community involvement, responsible tourism, and effective conflict mitigation, mountain gorillas can secure a stable and growing future.

The next few years will be decisive in determining whether this iconic species continues its remarkable comeback or faces renewed setbacks.

How You Can Help Combat Gorilla Poaching

You don’t need to be on the frontlines in Africa to make a real difference in the fight against gorilla poaching.

Here are practical, impactful ways to contribute:

- Donate to trusted organizations such as WWF, the International Gorilla Conservation Programme (IGCP), Gorilla Doctors, or the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund. Your support funds ranger patrols, snare removal, veterinary care, and community programs that directly reduce poaching threats.

- Choose responsible eco-tourism: Book gorilla trekking permits through official channels in Rwanda or Uganda. Tourism revenue provides sustainable income for local communities and finances park protection—far more effective than poaching ever could be.

- Avoid wildlife products: Never purchase or support items made from gorilla parts, bushmeat, or other endangered species. Educate friends and family about the devastating black market.

- Advocate and raise awareness: Share facts about gorilla conservation on social media, sign petitions for stronger anti-poaching laws, and support policies that address conflict and habitat protection in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Every action counts—your involvement helps ensure these gentle giants continue their remarkable recovery.

Why Choose GoSilverback Safaris for Your Gorilla Trekking

Choosing the right safari partner can make the difference between a trip that’s forgettable and one that’s truly life‑changing. Here’s why GoSilverback Safaris stands out as the ultimate choice for your gorilla trekking adventure in Uganda and Rwanda.

🦍 1. Expertise That Brings You Closer to the Gorillas

At GoSilverback Safaris, we don’t just book permits — we craft experiences.

Our team includes seasoned trekking guides with deep knowledge of gorilla behavior and the forests’ terrain.

They don’t just lead you — they interpret the jungle, helping you understand gorilla social structures, tracking signs, and how to observe these majestic animals respectfully and safely.

👉 Result: A more immersive, educational, and genuinely meaningful encounter.

2. Committed to Responsible Tourism & Gorilla Conservation

We are not onlookers — we are protectors.

GoSilverback Safaris works hand‑in‑hand with local communities and conservation organizations to ensure that your trek supports the very habitats you came to see.

We emphasize:

-

Respectful, minimum‑impact trekking

-

Community involvement and benefit sharing

-

Revenue going back to protect gorillas and local livelihoods

👉 Your safari becomes part of the solution, not the problem.

3. Safety, Comfort & Personalized Support

Your peace of mind matters. From the moment you book to the final farewell, we take care of details so you can focus on the wonder of the experience.

We provide:

✔ Pre‑departure briefing and essential trekking advice

✔ Transfer logistics to and from lodges

✔ Porter assistance (optional but very helpful)

✔ First‑aid–trained guides and support staff

👉 You trek with confidence — not worry.

4. Tailored Experiences That Suit Your Style

Whether you’re a seasoned adventurer or a first‑time traveler, GoSilverback crafts itineraries that match your preferences, pace, and budget.

We help you choose:

✨ Ideal trekking zones (Bwindi vs. Mgahinga vs. Volcanoes)

✨ Comfortable or luxury lodge options

✨ Complementary experiences (community visits, nature walks, birding)

👉 This isn’t a one‑size‑fits‑all trip — it’s your journey.

5. Unforgettable Moments Made for You

There’s a difference between seeing gorillas and connecting with them.

With GoSilverback:

-

You get prime positioning in your gorilla encounter

-

Guides help you anticipate and capture the best moments

-

You leave with stories — not just photos

👉 Memories that stay with you long after the safari ends.

Real Support From Real People

We’re not an impersonal booking engine — we’re real people invested in your adventure. Our client care team is responsive, knowledgeable, and ready to help you every step of the way.

Whether you’re asking about:

📆 Best time to trek

💰 Permit availability and pricing

🛫 Travel planning and packing advice

—we’re here to support you.

In Short — Why GoSilverback Safaris?

Because you deserve more than a tour.

You deserve a meaningful, professionally supported, ethically mindful, and deeply memorable gorilla trekking experience.

👉 Choose GoSilverback Safaris —

where your dream of seeing Silverbacks becomes an unforgettable reality.

Frequently Asked Questions

How many gorillas are poached yearly?

Direct targeted killings are rare (often fewer than 5 documented cases annually), but incidental snare-related deaths and injuries number in the dozens each year, especially in conflict areas of Virunga.

Do people still poach gorillas?

Yes. Although strict protection and ecotourism have reduced poaching, gorillas are still threatened by illegal hunting and snares, especially where patrols are weak or conflict occurs, like parts of eastern DR Congo. Poachers sometimes target them accidentally or for bushmeat and body parts.

What country in Africa has the most poaching?

While detailed numbers vary by species, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) faces some of the most intense wildlife poaching pressures due to ongoing conflict and limited anti-poaching enforcement.

How many silverback gorillas are left in the world in 2025?

As of 2025, there are about 1,063 mountain gorillas in the wild, including silverbacks leading family groups. Not all individuals are silverbacks (adult males), but this reflects the overall population size.

Who was killed by gorilla poachers?

A well-known mountain silverback named Rafiki was killed by poachers in Uganda’s Bwindi Impenetrable National Park in 2020, which was a major setback for conservation efforts.

Are mountain gorillas still endangered?

Yes—they are classified as Endangered by the IUCN, though their population has grown significantly due to conservation efforts.

Can tourism actually help protect gorillas?

Absolutely. Gorilla trekking permits generate millions annually for park management, anti-poaching, and local communities, creating strong economic incentives to protect the animals instead of poach them.

Your voice and actions matter—join the effort today.

Conclusion

Mountain gorillas have staged an extraordinary comeback: from a low of ~620 individuals in 1989 to over 1,063 today—a 73% increase—thanks to dedicated ranger patrols, international collaboration, innovative technology, and community engagement.

Yet poaching, especially through snares in conflict zones like Virunga, remains a persistent threat that can undo decades of progress.

The future is within reach. With continued support, responsible tourism, and global advocacy, populations could surpass 1,100 by 2030 and secure a thriving legacy.

Now is the time to act—donate, travel sustainably, spread awareness, and stand with the rangers risking their lives for these icons of biodiversity. Together, we can ensure mountain gorillas not only survive but flourish for generations to come.